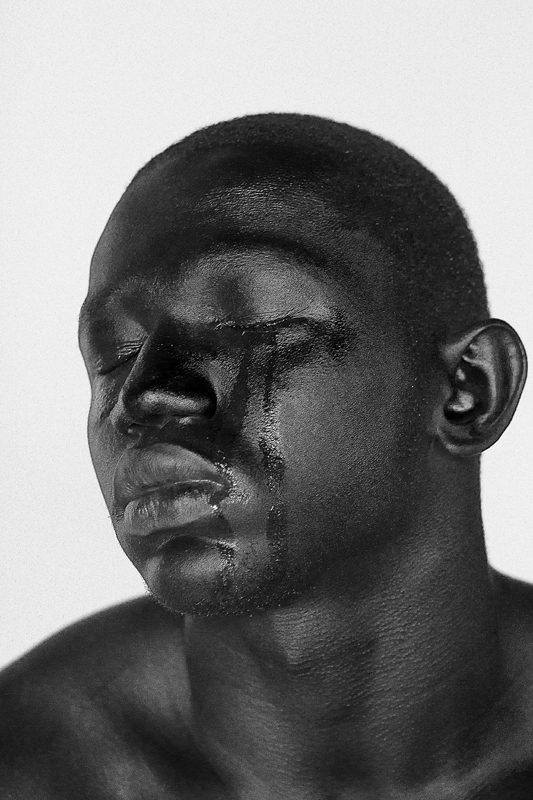

Black Art Feature: Shikeith

1.Curator of the Studio Museum of Harlem said Thelma Golden wrote that post Black artists were “adamant about not being labeled Black artists though their work was steeped, in fact deeply interested, in redefining complex notions of Blackness”. Do you agree with the concept of post Black art?

If we can ask what is art? than we should be able to ask what is black art? Are they separate but equal? Thelma Golden has been extremely pivotal in expanding discourse around race matters in institutional art. For myself the concept of post-black art can not be simplified to an evasion of blackness, or the end of an era but more so a conversation on a black persons “appropriate” aesthetic practice in the art world.

Developments in art periods have largely been attributed to the white artist, as to say no other ethnic groups practiced or contributed to genres such as abstract expressionism. There is a purity allocated to white artists that sets them up to be represented as primary, or straight to the point. It’s an oppressive structuring that asserts originality, value and high quality to one set of people in the totality of artists that ever existed. To me post-black art may have been a hypocritical response to the singular labeling and disregard of an obvious diverse collective of styles from black artists.

2.Do you feel obligated to create work that explores race in America?

In the early stages of my artistry I took it back to Africa in the style of my work. Keep in mind I had never been to Africa but I assumed I was obligated to such. In my schooling I was rarely exposed to other American Black contemporary artists, and was only presented a segment that focused on African art. I began creating beautiful things void of personal narratives. Race was not a topic because up until college I primarily engaged and lived with other black people.

Subsequently, one day as I walked across my college campus to my dorm I was called a ‘nigger’ by a group of white males. That moment ignited an internal battle of “what should I be shaping myself to be in order make the surrounding public comfortable?” It was a dilemma that manifested in contradictory patterns in my work. On one side I was producing bodies of work such as “Ode to Black” that addressed racism in fashion, while on the opposite featuring primarily white female models in my editorial imagery. I was confused; I did not know how to be creative and black at the same time.

But I needed to go through that, to get to where I stand now. As I continued to blossom I was able to not fear honesty in my artistry with disregard of former pressures. I am creating work influenced by my life, what I think and how I feel. In doing such the narratives around my work will continue to be race based because I’ll only experience this life as a black man.

3.Where does the symbolism of balloons and flowers in your art originate?

Currently, my work channels depressive periods I have endured in my emotional well-being. During those times I would have repetitive dreams in which flowers, and balloons were frequently part of the details. In my work I subtly juxtapose surrealism with my real life experiences as a black male because I am often questioning is this a dream or reality?

4.In order to re-examine the legacy of archaic stereotypes of black masculinity, do you feel it always necessary to depict the binary opposite in your work?

The full spectrum of the black male experience is not always realized in art, because of the lack of work characterizing the emotions of black men. Society, even within the confines of the black community, teaches the black man that he is not to seek full access of his emotions, often to prevent the appearance of weakness. With escalating criticisms of media portrayal of men of color, representation of men of color in art or film, and the fight to assess and prove the value of the bodies of men of color, exploring the dichotomies of black masculinity in my work is essential.

5.How does your work add to the ongoing public discourse on hyper masculinity in the Black community?

In the black male community many of our idealized traditions of how to raise a boy are not protecting us externally, or internally. In my work I do reference my experiences with homelessness as a result of not being considered “man enough”, as well as my indulging in respectability politics to distance myself from “those black guys”.

This especially applies to my younger years where I exhibited “stereotypical” characteristics of hyper black masculinity. Not because I aimed to represent a set of discriminatory behaviors, but rather I had fallen trap to evading my individuality. In my adolescence I learned to comply with these stigmatized notions to survive amongst other black boys. When I no longer represented what they deemed appropriate I was ostracized through physical and verbal abuse.

In 2013, I released a short art film entitled “TOM” in which the protagonist could easily be ambiguous to other black males. Is it the black male who exists in the realms of hyper masculinity, or is it the black male who has taken on roles of respectability politics? In all these are often the two choices many black men feel that have to take in order to survive in America. My work is a reflection of that internal battle all black men have to face when you’re not seeing things in black or in white but rather in grey. I totally stress the importance of projecting more individual voices and differences in the black male community.

6. What do you hope viewers will take from your exhibitions?

Recently, I experienced my second solo-exhibition “Somewhere over the _” and the response was very strong. I watched as people became overwhelmed with emotion, including myself from the sheer fact that my work was evoking such a reaction. That is one of the components I hope never dissolves. The interpretations of the work will always be different, but I hope to continue getting people to connect with the subject matter on an emotional level.

7.How do you feel art affects or influences the consciousness of Black America?

The great thing about photographs from earlier decades is that they tell the truth. Art is a very powerful tool that can be used to influence the mind of anyone. I think for Black Americans the Internet has assisted in our gaining access to illustrations of our history. For me a pivotal moment was my discovery of black people in paintings from the Renaissance, and Medieval periods. In those paintings I learned we were both esteemed and common civilians of Europe. That awakens you to a history of how rich of a culture we have had in this world. Art proves we have always been more than what initiated our history in America.

8.Do you feel that art is not respected in Black culture, or if there ever existed a time it was?

Creativity, and art practice in black culture reaches as far back to the high level sculptures of ancient Egypt; the rock paintings of sub-Saharan Africa; the folk art of American slave Harriet Powers; the Harlem Renaissance paintings of Jacob Lawrence, and the contemporary photography of Carrie Mae Weems. Black people love art and to say otherwise is a problematic cultural association.

And likely, the reason why black engagement with art that is accessible inside the confines of a gallery or museum is sometimes a troubling experience. Even for me– comfort walking around some spaces is questionable. I understand protecting work, but I have had many encounters with security following behind my every step in galleries. It’s not welcoming and feels like racial profiling, which is why many black people do not go into these spaces. For those reasons I plan on creating opportunities to exhibit my work within the dialogue it belongs.

9.Who are the artists which most influenced you.

When it comes to visual art I am largely influenced and inspired by the works of Duron Jackson, Glenn Ligon, Gordon Parks, David Hammonds, Kiki Smith, Shirin Neshat, Ann Hamilton and Kara Walker. As I continue to make films, I am looking to the work of Marlon Riggs, Robert Wilson, Melvin Van Peebles, and Oscar Micheaux. I love immersing in the work of all these folks their contributions have been so impactful.

10. So, when it comes to your latest film #blackmendream, How has the response been since releasing the film? Has your family seen your film and do they like it?

Honestly, it has been incredible–the personal emails I have received, commentary over social media, it has all been extremely touching. I am always appreciative of people taking the time to engage, and share my work. I will always be grateful for any support I receive. As far as my family they continually tell me how proud they are of me. Coming from where I am from this was not a likely path for a young, black male. So members of my family always go the extra mile to support me. My mother in particular loves to share things over Facebook!

11. What did this project do for you emotionally? How important is this film to you?

My work is always backed by my passion of delivering a strong message. #Blackmendream in particular was an emotional process from conception to completion. It is not an easy thing to break a cycle of restrictive emotionality, or getting strangers to express at the levels depicted in the film. Everything about this film is genuine, and raw. It was important to do something that would foster this open communication amongst black men. I feel like the film goes beneath the surface of dialogues we are used to partaking in regarding black manhood.

12. Do you plan on making this a series and asking black men these question all over the country?

The film was created as a social practice activity. To participate viewers are encouraged to utilize the hash tag to publicly respond to the set of questions asked during the film and engage in discourse about black male emotionality. That means no matter where you are, or who you are– you can connect with others under the hash tag #blackmendream. Also, I do have hopes of recreating a sculptural video installation the film has already taken the shape of during my recent exhibition but in a public art setting.

13. Was having them naked meant to show vulnerability? Why did you choose not to show their face?

The nudity in my work exploits the hypersexual gaze placed on black bodies to get individuals engaged. Subsequently, they recognize they’re observing a fragile, vulnerable subject. The rendering of their backs to the viewer has many layers and interpretations. To turn your back is a rejective posturing. I wanted to expose what it is like to be dressed in assumptions before opening your mouth to say hello.

14. What can we look forward to from you?

This month I made available on my website a limited edition art book, entitled “Somewhere over the _”. It’s my first book, and I am so proud of the truths I gained courage to explore inside of it. In my art there will be a continuation of using my experiences as a catalyst to evolve my work. I look forward to exhibiting more often and experimenting with new ways to engage with the community. I am going to keep pressing forth. I have realized what has worked for others, has never worked for me. Learning to accept that was another step on the ladder towards my goals.

For more of the artist please check out:

http://vimeo.com/shikeith/blac

http://shikeith.com/book.html

http://instagram.com/shikeith

Are there any other contemporary Black artists with work you are a fan of? Who are your favorite Black artists overall?